Overview

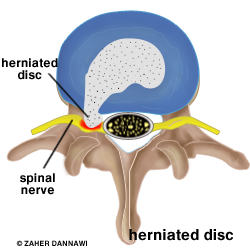

This is an extremely common condition, frequently referred to as a ‘slipped disc’. The central portion of the lumbar disc (nucleus pulposus) bulges through the surrounding fibrous tissue (annulus fibrosis) and may cause irritation or compression of an adjacent nerve (Fig 1). This often occurs in the presence of an abnormal or degenerate disc, which has a small tear in the annulus fibrosis.

Fig 1. A herniated disc (grey) causing irritation of a nerve root (yellow).

A lumbar disc prolapse may cause leg pain, with associated pins and needles, numbness and weakness. Occasionally the disc may compress the sac of nerves at the end of the spine called the cauda equina (see cauda equina syndrome), which may damage the nerves controlling bladder, bowel and sexual function.

In most patients the symptoms improve within six weeks with physiotherapy treatment and analgesics. If the pain persists or there is weakness in the leg or concerns about cauda equina compression then the diagnosis of a disc prolapse can be made with an MRI scan and surgical intervention would be indicated.

What other treatment options are there?

The majority of patient’s symptoms will resolve without interventional treatment and require simple analgesics and physiotherapy. If the pain persists despite these measures a confirmed disc prolapse may be treated with a nerve block, caudal epidural or surgery.

Nerve Root Blocks

This procedure is used when pain relief is required, yet surgery is not immediately indicated. It eases the pain while the disc prolapse resolves. (See Nerve Root Block).

Prior to surgery

Prior to surgery you will be explained the natural history of the condition (what is likely to happen without treatment). Most patients experience relief of symptoms without surgery. Other treatment options will then be discussed and the surgical procedure will be explained including the postoperative care and potential complications (see Complications), prior to you consenting to undergo the operation.

Surgery is indicated under following circumstances.

1. Central disc prolapse pressing on the nerves to the bladder or bowel (cauda equina syndrome)

2. Progressive weakness within the leg

3. Severe leg pain not responding to conservative measures within the first 6 weeks of onset

4. Persistent pain affecting activities at 6 weeks or more following non-operative measures

After surgery, 75% of patients with sciatica are expected to improve significantly. Approximately, 20-25% would improve but may have some minor persisting symptoms. About 5% of patients are not helped by the operation and 1% may even be worse off.

Surgery

A general anaesthetic is required and once this is administered the patient is placed on their front. An X-ray machine is used to localise the area of the spine that needs to be operated on. This allows the surgery to be made through a smaller scar and reduces the risks of scar tissue forming around the nerve and causing post-operative pain.

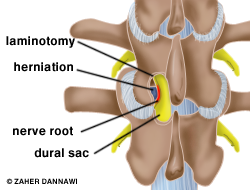

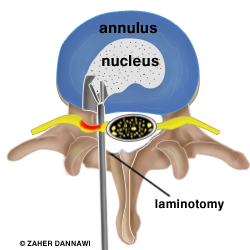

The muscles around the spine are moved out of the way, and a small hole or laminotomy is made in the soft tissues or bone to gain access to the prolapsed disc (Fig 2a and 2b).

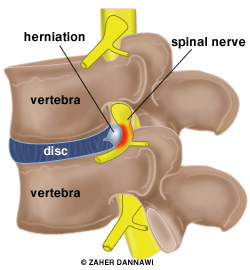

Fig 2a. Disc herniation (lateral view).

Fig 2b. laminotomy made to access the disc herniation.

The nerves are carefully reflected out of the way and the disc prolapse is removed in order to relieve the pressure on the nerve (Fig 3). The annulus is left in position.

Fig 3. Discectomy performed after reflecting and protecting the neural structures.

What are the risks of surgery?

Infection: The risk of infection is less than 1%. If you develop an infection it is most likely to be a superficial wound infection that will resolve with a short course of oral antibiotics. Occasionally an infection can spread deep into the disc space and vertebral bodies. If this occurs you may require a prolonged course of intravenous antibiotics or additional surgery.

Bleeding: Blood loss is usually minimal with a discectomy, although there is a small risk of developing a haematoma (blood collection) which could cause pressure on the thecal sac and necessitate an evacuation.

Wound healing problems: Wound healing problems can be due to local wound factors such as: stitch abscess, maceration, necrosis and pressure leading to disruption of local blood supply. Systemic factors leading to delayed wound healing include: Diabetes, obesity, smoking, alcoholism and poor nutrition. In the majority of cases the wound will eventually heal but may take longer than expected to do so.

Nerve injury : To expose your disc prolapse the nerve root needs to be retracted. In doing this there is a very small risk of physical damage to the nerve. This can lead to loss of nerve function, with persisting leg pain, weakness, and numbness. It is possible that a nerve injury could affect your bladder and bowel function. Nerve injuries are usually temporary, but may be permanent.

Dural tear : Occasionally the lining to the nerve (the dura) can be damaged causing the leakage of the fluid that surrounds the nerves (the cerebro-spinal fluid). Some tears are managed conservatively, whilst others require surgical repair. Patients who have had a dural tear may be asked to stay in bed for a short period of time following their operation. Occasionally a persistent leakage of spinal fluid occurs which may require further surgery.

Recurrent disc prolapse: A further disc material may prolapse through the same area of the disc as previous disc prolapse. This can occur at any time, but is most common in the first three months following surgery. A recurrent disc prolapse is treated in the same way as the original disc prolapse, and may require a repeat (revision) discectomy. The risk of a recurrent disc prolapse that requires further surgery is 5%.

Scar tissue: Scar tissue can form around the nerve and can mimic the symptoms of a disc prolapse. We will usually try to address this with injections rather than further surgery.

Failure to alleviate the pain: This can occur in less than 5% of patients and in less than 1% symptoms may get worse.

Further surgery on the spine: The degenerate disc may become a source of back pain in the future and spinal fusion may have to be considered.

DVT: Developing blood clots in the legs (deep vein thrombosis – DVT) is a risk of any surgery. We minimise this risk by using thrombo-embolic deterrent stockings (TEDS) and mechanical pumps. These pumps squeeze your lower legs, helping the blood to circulate. They are put on when you go to sleep and stay on until you start to mobilise. We encourage early mobilisation as this also helps to prevent DVTs.

Post operative care

On the evening of the surgery or the following day you will be able to mobilise with the help of the nursing staff. You will be seen by a physiotherapist prior to discharge home and encouraged to mobilise as much as possible. Plans will be made for physiotherapy treatment within the outpatient department.

How long until you are better?

When pressure is taken off a nerve the first symptom to improve is pain, which may be immediate. It takes a longer time for muscle weakness to improve. If there has been any muscle wasting (loss of muscle bulk) this frequently never recovers, even though the strength often does. The last symptom to improve is numbness, which sometimes never recovers fully. After surgery it is not uncommon to have various aches and pains in and around the wound, and in the bony pelvis, hips and thighs. These usually improve with time. For the first few weeks postoperatively, your sciatica may return because of nerve swelling.

It is very helpful to have seen a physiotherapist before your surgery and even more important to see one postoperatively. You can receive heat, ultrasound and massage, information on exercises and on how to move and how to build up your core [back and abdominal] muscles long-term in order to help best maintain the strength of your back.

Patients usually return to work between four to six weeks following surgery depending on their job.